The Disappearing Colorado Psychedelic Advisory Board

When voters approved a “magic” mushroom advisory board, a vanishing act likely wasn’t what they had in mind

Last November, Colorado voters made history by approving Proposition 122, the Natural Medicine Health Act. This ballot initiative was the first to pair psychedelic decriminalization with a regulated framework for psilocybin manufacturing, testing, and supervised administration.

Two years earlier, Oregon paved the way with two ballot initiatives. Measure 109 created a framework for the supported adult use of psilocybin. Separately, Measure 110 partially decriminalized many psychedelics and other controlled substances. But Colorado was the first state to combine decriminalization and regulation in a single ballot initiative.

Shortly after voters approved Proposition 122 last November, Colorado’s psychedelic community swung into action. It seemed everyone wanted a place on the governor-appointed Natural Medicine Advisory Board. Proposition 122 requires the board to make recommendations to state regulators on rules for implementing ballot measure language.

Various interest groups submitted slates of preferred board candidates to Governor Jared Polis. These groups included a local psychedelic nonprofit called the Nowak Society and “Natural Medicine Colorado,” a political group that promoted Proposition 122 with significant out of state funding. About $4 million came from New Approach, a D.C.-based lobbying firm that funded Oregon’s Measure 109 campaign.

Another multi-state lobbying group called the Healing Advocacy Fund, which has close ties to New Approach, interviewed potential board members for its list of preferred candidates. According to Denver activist Ashley Ryan, the Executive Director of the Fund’s Colorado branch, Natasia Poinsatte, conducted those interviews.

When Polis announced his board appointments on January 27, local activists saw few names they recognized. No one from the Nowak Society or Natural Medicine Colorado was appointed. Groups that had opposed Proposition 122, like SPORE and Decriminalize Nature Boulder, were also passed over.

The absence of familiar faces surprised many veterans of Colorado’s psychedelic community. Some became concerned the board members might lack familiarity with psychedelics and related policy issues.

According to the Nowak Society, “[w]hat remains unclear is how many of the 15 appointed have personal or professional roots with plant medicines and psychedelics. Sadly also, no one known to us in the Colorado plant medicine and psychedelic communities received an invitation to serve, even while many were interviewed for a seat.”

Since being appointed, the board has been shrouded in mystery. When Denver journalist Chris Walker contacted appointees to inquire about their backgrounds, he learned the governor’s office had prohibited them from speaking with the press or the public. This gag order was unexpected, partly because so many questions remained unanswered. But the greatest surprise was yet to come.

After its members were appointed, the Natural Medicine Advisory Board seemingly vanished and has remained largely invisible.

These events differ from what happened in Oregon two years earlier. On March 16, 2021, Governor Kate Brown appointed members to Oregon’s Psilocybin Advisory Board. Just two weeks later, on March 31, the Board held its first meeting.

There was no time to waste. It took months for Oregon board members to get to know each other, appoint board leadership, create subcommittees, and delegate tasks to those committees. Even with a generous two-year rule making period, the Oregon Board cut things close, leaving many details of the state psilocybin industry unexamined.

By comparison, Colorado’s Board has an accelerated eighteen-month rule making period, six months shorter than Oregon’s. Yet two months after being appointed, the Colorado Board has held no public meetings.

There is one important difference between the board appointment processes in Colorado and Oregon. Colorado’s board members had to be confirmed by the state Senate before starting their terms of service. With their accelerated timeline, one might think the Senate should have confirmed the board immediately. However, the Senate delayed confirmation hearings until mid-March.

The circumstances surrounding the delay are mysterious. On February 6, Chris Walker quoted Andy Bixler, communications director for Colorado’s Senate Democrats. According to Bixler, the confirmation process should have started almost immediately after Polis announced his selections in January.

“The Senate received these nominations earlier [last] week, and we anticipate they’ll be introduced into our system [soon],” said Bixler in early February. “From there, it usually takes a week or two to get nominees scheduled to testify for their confirmation hearings, after which the nominations will be considered before the full Senate on the floor.”

Bixler’s quotes suggest the Senate received the list of board appointments in late January, and confirmation could have been completed a few weeks later, by mid to late February, at the latest. But over a month went by before the Senate Committee on Finance quietly approved board appointees on March 14th and forwarded them for final Senate confirmation on March 17th.

Activists say they received no notice of the hearings, which also went unmentioned for a week by news outlets and social media. Activists had previously contacted the Senate to learn when it would confirm the board. But they received no response.

When Ryan first saw the list of board appointees, she wanted to know when the hearing was scheduled to show up and voice her concerns. Last month, she published a tweet expressing dismay at the lack of a hearing date.

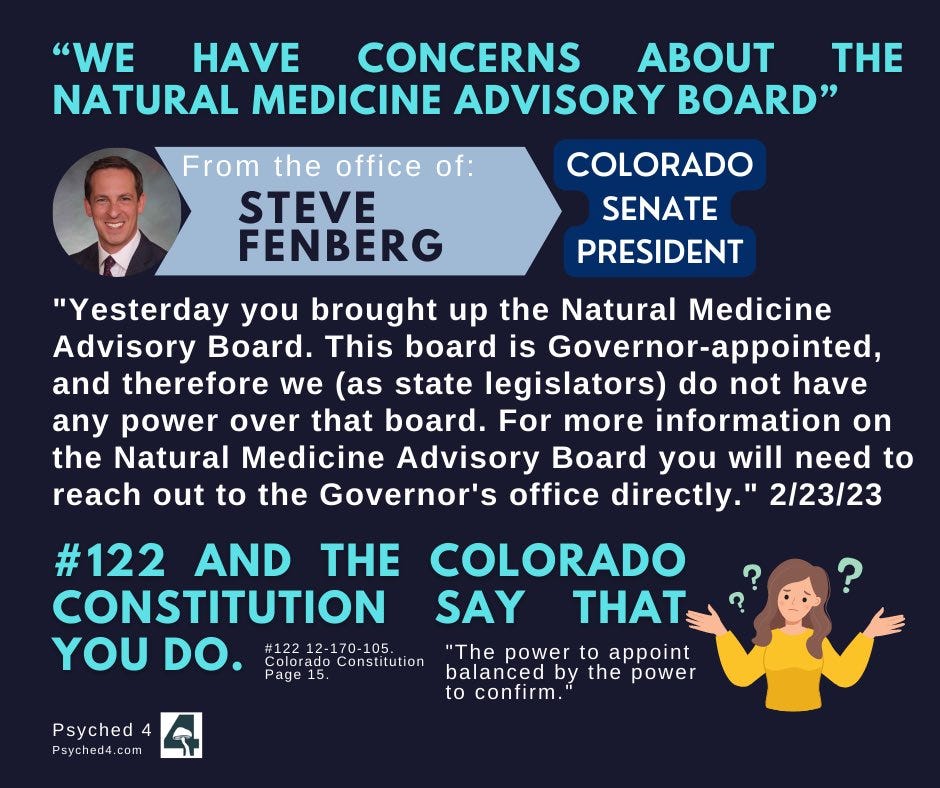

According to Twitter user Psyched4News, activists asked Colorado Senate President Steve Fenberg about the hearing. Fenberg reportedly told them that because the Board is governor appointed, the Senate has no power over it. He then referred them to the Governor’s office.

During a Boulder, Colorado town hall meeting on February 13, Fenberg invited the public to call, email, or visit his office to discuss the Natural Medicine Health Act. “There are definitely things that are said on the internet that you could get a much better sense by giving our offices a call, or sending us an email, or just coming down to the capitol visiting with us,” said Fenberg. “We are more than happy to talk through what we are and what we are not working on and what the intent is of that work.” However, according to Ryan, she and other activists have visited the Capitol for several weeks, and Fenberg has not responded to their requests for a meeting.

When I contacted Fenberg’s office on Tuesday to inquire about the Senate confirmation hearing, I was told it had already taken place. A representative said Fenberg was collecting names of those who wish to meet and will hold meetings once he has something to discuss regarding the Natural Medicine Health Act.

I contacted the Department of Regulatory Agencies (DORA) to learn when the board’s first meeting might be held. Agency spokesperson Katie O‘Donnell said board members are undergoing training, “and the hope is to meet in the next month or so, pending schedules and coordination with board members.” Things now appear to be moving forward. But no meeting date or agenda have been set. This could cause serious problems for Colorado’s psychedelic industry. Recent events in Oregon may foreshadow what’s to come.

In the past few months, Oregon’s psilocybin program hit several roadblocks. The Health Authority division overseeing it, Oregon Psilocybin Services, nearly went bankrupt and asked taxpayers for $6.6 million to stay afloat for one calendar year. Meanwhile, likely due to high licensing fees, few aspiring businesses have applied for licenses, and no psilocybin service centers have opened. Accordingly, no one knows when psilocybin will become available, and hundreds of graduates from facilitator training programs have nowhere to work. Prominent schools and service centers like the Synthesis Institute are going out of business. Some wonder whether the industry has any future at all.

The implementation period for Proposition 122 is the time to plan for and avoid these outcomes, and with a cloud hanging over Oregon’s program, one might think the Colorado Board should get down to business immediately. As I’ve written previously, compared to Oregon’s Measure 109, Proposition 122 leaves more unresolved issues for state regulators and the advisory board to figure out. With rapidly approaching deadlines, there’s no time to lose.

According to the Natural Medicine Health Act, the Colorado Board must make recommendations to DORA no later than September 30, 2023, only six months from now. By the time the board meets, it may have five or fewer months remaining. The group must consider a wide array of issues in this rapidly diminishing timeframe, including—but not limited to—the following:

Accurate public health approaches regarding use, effect, and risk reduction for natural medicine and the content and scope of educational campaigns related to natural medicine;

Research related to the efficacy and regulation of natural medicine, including recommendations related to product safety, harm reduction, and cultural responsibility;

The proper content of training programs, educational and experiential requirements, and qualifications for psilocybin facilitators, the licensed professionals who will dispense psilocybin in Colorado;

Affordable, equitable, ethical, and culturally responsible access to natural medicine and requirements to ensure the regulated natural medicine access program is equitable and inclusive;

Appropriate regulatory considerations for each natural medicine and whether additional substances (mescaline, ibogaine, and dimethyltryptamine) should be added to the regulated psilocybin program;

Requirements for accurate and complete data collection, reporting, and publication of information related to the implementation of the regulated psilocybin program; and

All rules to be produced by DORA as required by Proposition 122.

Making recommendations to DORA on all these topics may seem an impossible task, even if the Colorado Board had convened immediately after being appointed. Why then did the board seemingly vanish, and why were its confirmation hearing and other activities so heavily concealed?

Some believe the board’s disappearance and delayed confirmation were intentional, giving lobbyists time to schmooze with regulators and push their agendas without the spectacle of public meetings.

During the Oregon rulemaking process, the Healing Advocacy Fund (which shares leadership with the New Approach PAC that funded the Proposition 122 campaign) met frequently with state regulators and the governor’s office. Governor Brown’s staff seemed proud of the Fund’s close involvement with Measure 109’s implementation. Much of its assistance came through closed door meetings with Health Authority officials and Oregon Board leadership.

During one meeting, Oregon board member Kim Golletz raised concerns regarding private meetings between the state Health Authority and the Healing Advocacy Fund. Golletz suspected that the Fund’s Executive Director Sam Chapman was orchestrating votes by contacting board members individually between meetings. She felt this practice violated transparency rules prohibiting board members from discussing business outside public view.

Last year, Golletz’s suspicions were confirmed by emails showing behind-the-scenes collaboration between the Healing Advocacy Fund, Oregon board members, and officials at the Oregon Health Authority. Specifically, the Fund met with board members Todd Korthuis and Chris Stauffer to coordinate plans for data collection from Oregon psilocybin clients.

Ultimately, Golletz’s questions and concerns went unanswered, and the Healing Advocacy Fund continued to influence Oregon’s psilocybin rules behind the scenes. Its Colorado branch, led by Natasia Poinsatte, is already hard at work.

Poinsatte, a director at political marketing firm RBI Strategies & Research, is Chapman’s Colorado counterpart. According to Ashley Ryan, in addition to interviewing candidates for the Healing Advocacy Fund’s list of preferred board candidates, Poinsatte attends meetings in Governor Polis’ office.

While Ryan and other activists waited unsuccessfully to speak with legislators at the Capitol, Poinsatte has reportedly been welcomed into its executive chambers. On March 15, Ryan filmed Poinsatte leaving one of those meetings. Poinsatte did not return Psychedelic Week’s request for comment.

There are several possible explanations for the Colorado Board’s disappearing act. Perhaps the delay was an oversight. Alternatively, regulators and the Healing Advocacy Fund might wish to delay board meetings, which draw media and public attention. While voters wait to learn what happened to their advisory board and ballot initiative, lobbyists like Poinsatte reportedly meets with government officials, and work that should occur in public may already be proceeding in secret.

Perhaps the board’s real magic trick is not its disappearance but the illusion of a democratic implementation process for the Natural Medicine Health Act. Hopefully that’s not the case.

At the confirmation hearing on March 14, board candidates appeared to have sincere hopes for the program’s success. DORA Executive Director Patty Salazar described them as immensely qualified and one of the most diverse boards in the state.

It’s too early to tell whether the board will be given the time and latitude to have more than a symbolic impact. But its delayed confirmation and convening are not exactly a propitious start.

*The views expressed on Psychedelic Week do not represent the views of POPLAR at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School or the Florida State University College of Law. Psychedelic Week is an independent project unaffiliated with these programs and institutions.

Mason Marks, MD, JD is the Florida Bar Health Law Section Professor at the Florida State University College of Law. He is the senior fellow and project lead of the Project on Psychedelics Law and Regulation (POPLAR) at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School and an affiliated fellow at the Information Society Project at Yale Law School. Marks teaches drug law, psychedelic law, constitutional law, and administrative law. Before moving to Florida, he served on the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board where he chaired its Licensing Subcommittee. Marks has drafted drug policies for state and local lawmakers. His forthcoming book on psychedelic law and politics will be published by Yale University Press. He tweets at @MasonMarksMD and @PsychedelicWeek.