Teaching Psychedelic Law

A course on psychedelic law starts at Florida State University. Likely the world's first.

Today, I was supposed to start teaching a new course called Psychedelic Law at Florida State University. As far as I know, it’s the first course of its kind offered by a university or law school, perhaps anywhere in the world.

Unfortunately, Hurricane Idalia intervened. As the hurricane approached Tallahassee, Florida, the university cancelled classes so students and staff could prepare for inclement weather. Hopefully, everyone stays safe.

With classes on hold, I thought it would be interesting to discuss the process of developing and implementing a psychedelic law course. Its roots extend back to my legal education and examples set by outstanding teachers.

When I graduated from Vanderbilt Law School in 2015, psychedelic science and policy were heavily stigmatized. At the time, teaching or enrolling in a course on psychedelic law would have seemed impossible.

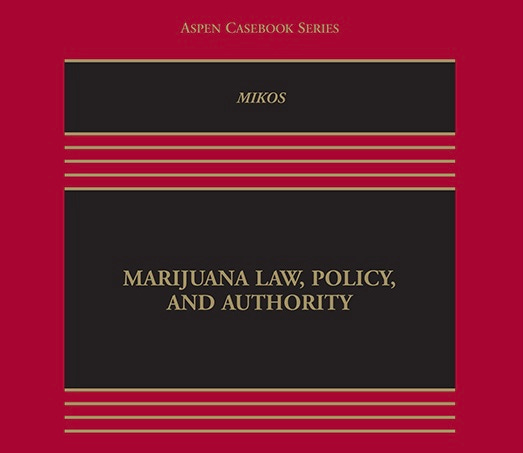

However, Vanderbilt was a trend setter in controlled substances law. Professor Robert Mikos offered one of the earliest courses on marijuana regulation. He also wrote one of the first marijuana casebooks, the fancy bound volumes law students carry between classes.

I learned a lot about drug regulation from Professor Mikos’s timely book and articles like On the Limits of Supremacy: Medical Marijuana and the States' Overlooked Power to Legalize Federal Crime. His thoughtful analysis of seemingly taboo topics was inspiring.

Though Vanderbilt lacked a course on psychedelics, I wrote a paper about them for Professor Ellen Wright Clayton’s course on bioethics and the law.

Clayton is an accomplished physician-scientist, attorney, and professor of pediatrics, law, and health policy. Not only did she create space for me to develop my academic interest in psychedelic law, she modeled exemplary teaching.

Professor Clayton’s students had significant autonomy. We could write papers on virtually any bioethics topic. She encouraged us to present our work in class before our peers, and we frequently had spirited debates on controversial medico-legal issues. It was empowering, and the paper I wrote launched my career in psychedelic law.

If not for Professors Mikos and Clayton, and other Vanderbilt faculty like Sean Seymore, Owen Jones, and Terry Maroney, my psychedelic law course would not be possible. Each professor blends law, science, and technology in thought provoking ways. They gave me the confidence to take intellectual risks and pursue what interests me most.

Years later, legal attitudes toward taboo topics like cannabis have changed. Some of the largest and most prestigious law firms now have teams devoted to marijuana regulation. Most U.S. states have legalized medical or adult use cannabis, and the Biden administration could reschedule cannabis this year.

Though medical research on psychedelics is progressing rapidly, psychedelics are years behind cannabis when it comes to acceptance by the legal community. A few law firms have taken interest, but for the most part, psychedelic law is the domain of specialized “boutique” firms. Some cannabis-focused attorneys increasingly add psychedelics to their list of practice areas. One innovative firm, Calyx Law, has made psychedelic patents a primary focus.

It won’t be long before larger firms grab onto this trend because psychedelics are big business. In this growing multi-billion-dollar industry, the companies development psychedelic products and services require knowledgeable counsel. As do state and federal agencies like the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the U.S. Patent Office, and state health departments.

Hospitals and healthcare providers are learning to safely integrate psychedelics into medical practice, while cities and states experiment with regulating or decriminalizing these substances. Meanwhile, the rights and practices of Indigenous communities who use psychedelics may be threatened and exploited.

For these and other reasons, it’s important to train lawyers to understand the complex legal landscape of what many call the psychedelic renaissance, a period of growing interest in researching, commercializing, and consuming psychedelics.

After observing a lack of relevant legal research and education, my colleagues at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School and I co-founded the Project on Psychedelics Law and Regulation (POPLAR) in 2021. POPLAR was the world’s first academic initiative focused on psychedelic law and ethics. We produce academic scholarship, host educational events, train researchers, and support community based organizations.

Alongside POPLAR, I’ve taught a yearly course called Drug Law, which combines FDA law and DEA regulation. Students learn about the FDA’s origins and how Congress increased its powers after several public health tragedies. They study the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) of 1970 and Nixon’s subsequent creation of the DEA. I typically devote two class sessions each to cannabis, opioids, and the war on drugs, and one class to psychedelics.

But this year, thanks to Florida State University, I can offer a course devoted entirely to psychedelic law. It’s a unique and fascinating area that combines health law, criminal law, business, and intellectual property with facets of constitutional law, including federalism, interstate commerce, freedom of thought, and the free exercise of religion.

Psychedelic law requires a broad understanding of the regulated substances, including their research and medical applications, their traditional use by Indigenous communities, and emerging uses by newer psychedelic churches.

Students must study a variety of statutes and state and federal agencies. Research on psychedelics is governed by the FDA and the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. Marketing and commerce involve federal agencies like the Federal Trade Commission, the Internal Revenue Service, and state agencies like the Oregon Health Authority. Religious use invokes federal laws like the Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) and the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA). In addition to federal statutes and the Constitution, international treaties play an important role.

Practitioners of psychedelic law must also understand the complex patchwork of state and local legislation. Only four years ago, Denver, Colorado became the first U.S. city to decriminalize a psychedelic substance (psilocybin). Today, there are over fifteen other jurisdictions, including large cities like Seattle and Washington, DC, that have decriminalized psilocybin and other psychedelics.

Less than three years ago, in 2020, Oregon became the first state to decriminalize psychedelics and start a regulatory process for the supervised use of psilocybin (often called supported adult use). Oregon psilocybin service centers opened for business this summer.

Last November, Colorado voters followed Oregon’s example. They took decriminalization further and will open psychedelic “healing centers” in 2025. Other states, including California and Massachusetts, are considering similar legislation.

Students in Psychedelic Law will study these and other legal developments. They’ll learn about ongoing efforts to reschedule psilocybin, lawsuits to gain access for people with life threatening illnesses, and federal efforts to decrease barriers to psychedelic research. They’ll engage with guest speakers representing all facets of the psychedelic ecosystem, including many practicing attorneys.

Like my classmates in Professor Clayton’s bioethics course, students in Psychedelic Law will write substantial legal research papers on topics of their choice. Those interested in publishing their work will receive guidance to help ensure their success.

I hope more schools will offer courses on psychedelic law, part of the emerging field of drug law, which deserves greater recognition. Other professors and I are working to bring attention to this important discipline. They include legal scholars like Jennifer Oliva and Taleed El-Sabawi, whose important article The ‘New’ Drug War will be published soon in the Virginia Law Review.

As the semester progresses, I’ll report back on teaching Psychedelic Law. For now, I look forward to the challenging topics we’ll discuss and the engaging debates we’ll have. Follow Psychedelic Week for more updates.

*The views expressed on Psychedelic Week do not represent the views of Harvard University, POPLAR at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School, Florida State University, or the Florida State University College of Law. Psychedelic Week is an independent project unaffiliated with these programs and institutions.

Mason Marks, MD, JD is a Visiting Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. He is also the Florida Bar Health Law Section Professor at Florida State University, senior fellow and project lead of the Project on Psychedelics Law and Regulation (POPLAR) at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School, and an visiting fellow at the Information Society Project at Yale Law School. Marks teaches constitutional law, administrative law, drug law, and psychedelic law. Before moving to Florida, he served on the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board where he chaired its Licensing Subcommittee. Marks has drafted drug policies for state and local lawmakers. His forthcoming book on psychedelic law and politics will be published by Yale University Press. He tweets at @MasonMarksMD and @PsychedelicWeek.