Oregon Psilocybin Emails Show Secret Data Collection Plans

Health authority repeatedly skirts privacy protections of state psychedelic law and rejects advice of psilocybin board and rules advisory committee.

Last Friday, I received a batch of emails from the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) in response to a public records request. The emails reveal close collaboration between the state agency, lobbyists from the Healing Advocacy Fund, and members of the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board. This group has been working covertly to mandate data collection from clients in Oregon’s nascent psilocybin program.

The emails flesh out the story I told in a November 2 article for Wired, Seeking Psychedelics? Check the Data Privacy Clause. Read the article to understand the risks of collecting data from psilocybin clients. In this post, I’ll share the highlights from OHA’s emails.

While researching the Wired article, I learned about a secretive data analytics program at Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU) called the OPEN Project. Participating companies, researchers, and representatives of OHSU declined to confirm its existence.

The OHA’s emails reveal what may be the project’s origin. In an email from January 5, 2022, Angela Albee of Oregon Psilocybin Services introduces Todd Korthuis, an OHSU researcher and Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board member, to Chris Olson and Britt Rollins who lead the National Psychedelic Association.

“I know you are having data collection discussions and thought it may be helpful to introduce you to Britt and Chris from the National Psychedelic Association,” says Albee, who then forwards the email to Sam Chapman and Jack Dempsey of the Healing Advocacy Fund, a lobbying firm funded by the New Approach PAC. “Just keeping you all in the loop on data collection,” says Albee to the lobbyists. “Let me know if you want me to loop you in with anyone as well,” she offers.

The Healing Advocacy Fund and its donors at New Approach PAC are not the only ones interested in amassing data from Oregon’s psilocybin clients. In a 2021 interview, George Goldsmith, the CEO of pharmaceutical company Compass Pathways, told journalist Shayla Love he sought access to psilocybin client data when contacting OHSU researchers in November 2020.

Fast forward to August 2022, and OHA’s emails show that plans for data collection are well underway. An August 3 message from New Approach’s Dempsey to the OHA’s Albee confirms their meeting to discuss data collection later that day. The agency’s Senior Recruiter Cynthia Phipps-Roman is copied, possibly reflecting plans to hire staff related to data collection. “Attached are two documents that should help inform the conversation,” says Dempsey. “The first is a draft proposal from OHSU and the second is a legal analysis,” from the Healing Advocacy Fund.

Dempsey’s proposal sheds light on the secretive OPEN Project (the Oregon Psilocybin Evaluation Nexus), which aims to collect detailed information on the psychedelic experiences of all psilocybin clients in Oregon. In the proposal, Dempsey and the Healing Advocacy Fund ask for $200,000 in start-up costs and $500,000 per year to operate the program.

The following day, Korthuis sends an email to Albee with a pitch letter he’s been sending to potential donors. Dated July 24, 2022, the letter opens with “Dear Friend, thank you for considering a contribution to the . . . (OPEN) project,” and closes with “[c]ontributions of any amount will contribute to our total goal of $330,000 during a 6-month start of period.” The pitch names other Psilocybin Advisory Board members as investigators in the project, including Dr. Chris Stauffer of OHSU and the VA Portland Health Care System, and Alissa Bazinet, a psychologist who directs research and development at a Portland ketamine clinic. To date, neither have revealed their participation to the public or the Psilocybin Advisory Board.

Despite their enthusiasm for data collection, Korthuis, the Healing Advocacy Fund, and their collaborators faced a problem. The client data they want is not easily accessed under Measure 109, the ballot initiative that voters approved to create Oregon’s psilocybin program.

On September 20, Albee emails the Healing Advocacy Fund asking Dempsey to tell Korthuis it would be impossible to require data collection from all psilocybin clients without passing a new law. “I think he needs to be aware that it would take statutory changes before licensees would be required to share client data, even de-identified data,” says Albee. “Does he understand this?” she asks. In a separate email sent that day, Albee urges Korthuis to work with the Healing Advocacy Fund on new legislation to require client data collection and report back to her. She offers to analyze any draft statutory language and provide support from OHA’s government relations team.

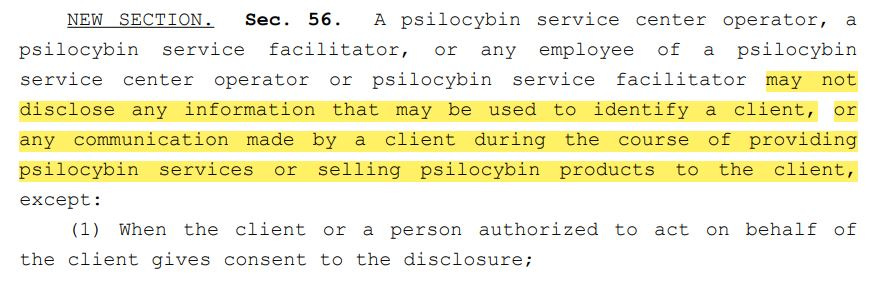

From the perspective of those who wish to mine data from psilocybin clients, Measure 109 poses challenges because it contains robust confidentiality protections for clients. Section 56 states that client communications cannot be disclosed outside psilocybin service centers, nor can any information that might be used to identify clients. That means anything clients say, write, or even gesture, while receiving services cannot be disclosed to OHA or anyone else, including Korthuis, Stauffer, and their team at OHSU.

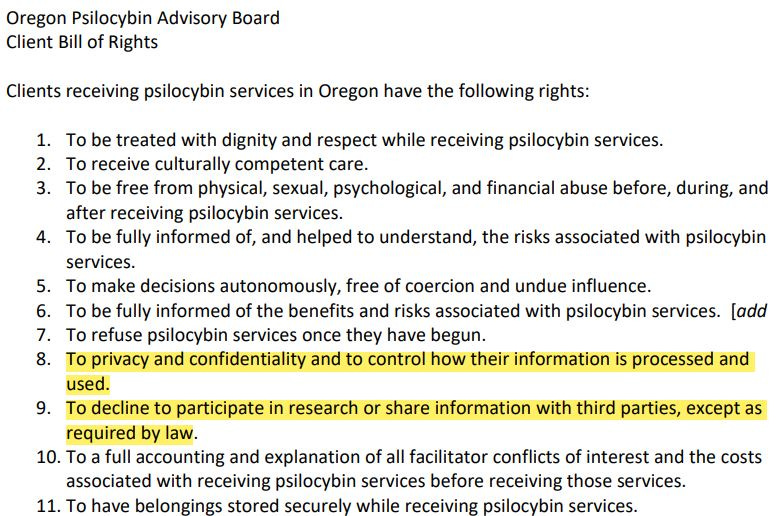

In May and June, the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board recommended rules for implementing Measure 109’s confidentiality section. In May, the Board unanimously approved giving clients the right to control how their data is processed and used and to decline to participate in research or share information with third parties.

In May, the Board also recommended duties for psilocybin facilitators, including a duty of confidentiality, which required them to “attempt to maintain the confidentiality of client information to the greatest extent possible.”

In June, the Board unanimously approved a Statement on Data Collection, which warned clients of the risks of sharing their data with third parties outside service centers, including the potential for deidentified data to reveal their identities and their participation in Oregon’s services.

Shortly after meeting privately with Korthuis and the Healing Advocacy Fund in August to discuss data collection, Albee and the OHA published September draft rules for the psilocybin program. Despite having followed many, if not most, of the Advisory Board’s recommendations, the OHA omitted client data rights, the facilitator duty of confidentiality, and the Statement on Data Collection. Moreover, in its statement to the public regarding its rules, the OHA highlighted several aspects of the rules but made no mention of the rejected data protections.

Despite Albee’s acknowledgement that mandatory data collection, including collecting deidentified data, was impossible without passing a new law, the OHA found what it appears to believe is a workaround. Instead of forcing facilitators to disclose client information to OHSU, the agency will force clients to agree to share their information with third parties as a condition of participating in the psilocybin program. Specifically, the OHA modified the informed consent document approved by the Board. Rather than warning clients of the risks of sharing deidentified data, it now requires clients to consent to sharing deidentified data with people and institutions outside service centers for “research and other purposes.” In other words, one month after meeting privately with Korthuis and the Healing Advocacy Fund, the OHA’s rules opened the door for their data collection plans, which continue to be kept a secret.

In September, the OHA convened its Rules Advisory Committee (RAC) to provide feedback on the agency’s rules. According to RAC member Rose Moulin-Franco, the obvious lack of data protections was concerning. “I along with every single member of the RAC advised them to give clients the right to opt out of data collection and record keeping,” recalls Moulin-Franco in a LinkedIn post from November.

Despite negative feedback from the RAC, the OHA doubled down in its second draft of the rules published in November. “The second round of drafts just dropped,” said Moulin-Franco, “and this unethical data collection and forced record keeping on adults 21 and over who are not required to have a medical diagnosis to access services, are exactly the same as the first draft we protested.” Her comments allude to the fact that Measure 109 is not a medical program, and most of the OHA’s rules reflect that. For instance, the rules prevent psilocybin facilitators from diagnosing or treating health conditions, prohibit service centers from being located within healthcare facilities, and bar facilitators from practicing the privileges of other licensed professions, including medicine and psychotherapy, when providing psilocybin services.

However, some board members like Korthuis have attempted to shift the program in a medical direction, turning a program focused on non-medical access to psilocybin into something voters didn’t anticipate or ask for, a research program to evaluate its effectiveness as a medical therapy. While publicly voting with other board members to create strong client confidentiality protections, Korthuis and Stauffer worked secretly to undermine the board’s recommendations.

Throughout November, the OHA solicited public comments on the latest draft rules. The agency will receive written comments at publichealth.rules@odhsoha.oregon.gov until Monday, November 21st at 5pm Pacific. During three live comment sessions last week, the public expressed concerns over forcing clients to agree to share deidentified data. Prema Sagara explained how the market for deidenified data is a multibillion dollar industry, calling OHA’s deidentified data rule “one of the most unjust and one of the most shady.” Sagara added, “transparency is needed on this, and a change to the rule.” Another speaker referenced the U.S. history of experimenting on marginalized communities without their consent, in atrocities like the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, and profiting from research without permission, in cases like the scandal involving Henrietta Lacks.

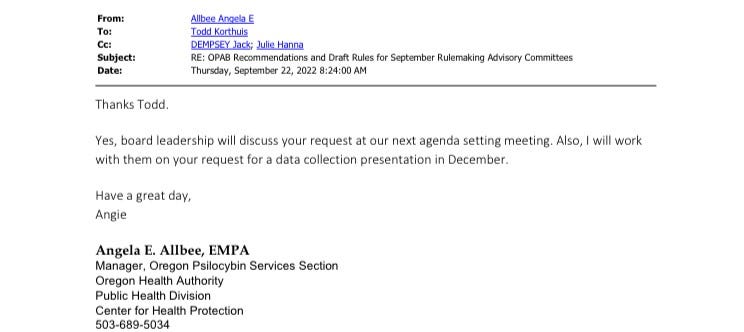

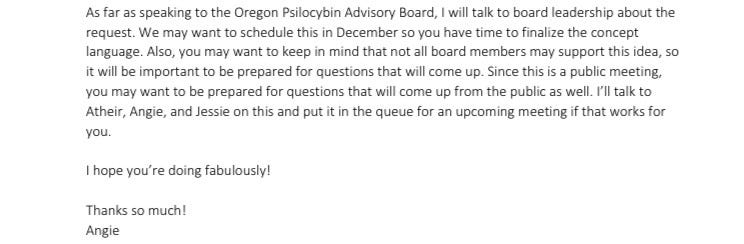

Emails show that Korthuis plans to reveal his data collection project at the Psilocybin Advisory Board’s December 9 meeting, more than two weeks after the OHA’s November 21 deadline for public comments, and three weeks before OHA’s deadline for publishing its final rules.

Despite exchanging emails in September, Albee and Korthuis agreed to hold the data collection discussion in December, after public comments close. According to Albee, postponing the discussion gives Korthuis time to polish the language. In another September email, she urges him to prepare (three months in advance) for questions from the public and other board members who might not approve of his data collection plan.

Pushing the discussion to December also means the public will have no means of responding to what Korthuis says because the OHA will disregard comments received after November 21.

The disclosed OHA emails reveal a close working relationship between the agency, lobbysists at the Healing Advocacy Fund, and members of the Psilocybin Advisory Board. Until now, their collaboration on mandatory data collection and analysis had been hidden from public view.

What do you think? Should the OHA revise its rules and follow the board’s initial recommendations on protecting client information? Should the agency extend the deadline for public comments in light of these revelations and Korthuis’s upcoming presentation? Perhaps the OHA should extend the deadline for public comment until December 15, 2022, giving people an opportunity to respond. Many stakeholders already object to mandatory data collection. But the secret web of relationships behind the “OPEN Project” may cast existing concerns in a new light.

*The views expressed on Psychedelic Week do not represent the views of POPLAR at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School or the Florida State University College of Law. Psychedelic Week is an independent project unaffiliated with these programs and institutions.

Mason Marks, MD, JD is the Florida Bar Health Law Section Professor at the Florida State University College of Law. He is the senior fellow and project lead of the Project on Psychedelics Law and Regulation (POPLAR) at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School and an affiliated fellow at the Information Society Project at Yale Law School. Marks teaches constitutional law, administrative law, drug law, and psychedelic law, . Before moving to Florida, he served on the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board where he chaired its Licensing Subcommittee. Marks has drafted drug policies for state and local lawmakers. His forthcoming book on psychedelic law and politics will be published by Yale University Press. He tweets at @MasonMarksMD and @PsychedelicWeek.

This is a shameful thought that would even cross these peoples minds. It is unethical and immoral to even think of breaching contract and putting personal information out there. People are not lab rats. These are people who are healing from mental illness and traumas. It is potentially adding more traumas as it is a full on violation. Shame on you for eve. Thinking this would be ok.