Psychedelic Week for December 18, 2022

Funding state psychedelic programs, next steps for Colorado's Natural Medicine Health Act, lessons from Portland's Shroom House, and recordings of recent psychedelic events

As the New Year approaches, 2022’s psychedelic news is winding down. This week I focus primarily on two main issues: How states are financing their psychedelic programs and what lies ahead for Colorado’s Natural Medicine Health Act. I discuss Portland’s Shroom House and link to recordings of recent psychedelic events on Informed Consent and Conflicts of Interest.

I created this week’s images using Midjourney.

Funding State Psychedelic Programs Is Expensive

On December 9th, the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board held its final meeting of 2022. In June, the Board made recommendations to the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) on rules for implementing Measure 109, the Oregon Psilocybin Services Act. The OHA published its latest draft rules in November and will publish final rules by year’s end.

At the start of the meeting, Angela Albee, who runs OHA’s psilocybin services division, made sobering remarks regarding funding. Her department is running out of money, and its priority for Oregon’s upcoming legislative session is to stay solvent.

“We don’t think we’ll have enough licensees to support our budget, and we’re asking for additional state general funds to avoid any kind of increases to licensing fees,” said Albee, who provided few specifics. Agency documents reveal that OHA seeks $6.6 million to run its psilocybin program for one year, starting July 1, 2023. In a related request, the OHA seeks $800,000, part of which will fund accreditation of psilocybin testing labs.

When Measure 109 was pitched to voters in 2020, it was billed as a self-sustaining program. Following a two-year implementation period, which ends this month, taxes and license fees would fund its entire operation, estimated to cost $3.1 million annually. However, the OHA won’t start accepting license fees until January 2, and most psilocybin businesses won’t open until later next year, which could delay the collection of taxes to support OHA’s administration of the program.

It’s unfortunate that the agency must request additional public funds. However, raising license fees would also be undesirable. The agency’s draft rules drew criticism for proposing high license fees. Under these rules, most psilocybin manufacturers, testing labs, and service centers will pay $10,000 annually, and most psilocybin facilitators will pay $2,000 a year. Advocates worry these fees will deter many businesses from opening, which will exacerbate the OHA’s funding problem and limit the diversity and availability of psilocybin services.

Some have asked the OHA to reduce fees for psilocybin facilitators, even if that means raising fees associated with other businesses. Interestingly, Measure 109 does not require facilitator training programs or their instructors to be licensed, which could have provided additional funds to the program. Their lack of contributions has prompted further criticism, especially because these businesses could be more profitable than psilocybin manufacturers and service centers, which will be heavily impacted by Section 280E of the Internal Revenue Code. The program’s final license fees will be revealed when the OHA publishes final rules later this month.

As Measure 109’s two-year rulemaking phase comes to a close, the eighteen-month implementation period for Colorado’s Proposition 122 begins. This ballot initiative, also called the Natural Medicine Health Act, poses a different set of funding challenges.

Perhaps in response to Oregon’s anticipated budget shortfall, Proposition 122 allows Colorado’s governing agency, the Department of Regulatory Agencies (DORA), to “seek, accept, and expend any gifts, grants, donations, loan of funds, property, or any other revenue or aid in any form” to support its regulated psilocybin program. These contributions can come from any source, including private donors. That means any organization could donate to the “regulated natural medicine access program fund,” including corporations, drug companies, law firms, lobbyists, philanthropists, or the political campaign that promoted Proposition 122 (Oregon’s Measure 109 established the Psilocybin Control and Regulation Fund to support the state’s psilocybin program. But there was no provision for the Oregon Health Authority to seek and accept private funding).

Though Proposition 122’s funding arrangement might help avoid a shortfall like Oregon’s, it raises other concerns. By paying into Colorado’s regulated access program fund, private donors could effectively pay the salaries of regulators who oversee and make rules for the psilocybin program. Because deposits into the fund would not constitute campaign contributions, it’s unclear to what extent they would be publicly disclosed.

Without clear guidelines in place, donor contributions could serve as a quid pro quo for implementing certain policies in Colorado. To prevent that from happening and build public trust, DORA should establish clear rules for evaluating, disclosing, and rejecting potential contributions to the fund. Proposition 122 does not require DORA to seek or accept contributions, giving the agency discretion to set its own policies, which could include foregoing private contributions altogether.

As more states consider implementing psychedelic laws, they’ll grapple with ways to fund the resulting regulated programs. They should keep Oregon’s budget shortfall in mind while also weighing the risks of accepting private funds.

Oregon’s Measure 110 illustrates a third possible approach to funding state psychedelic programs. Passed alongside Measure 109 in 2020, Measure 110 removed criminal penalties associated with possessing small amounts of many controlled substances, including psychedelics. Those in possession of substances within the legal limits pay a $100 civil penalty or undergo a health assessment by an addiction recovery center. To fund these services, Measure 110 siphons money from Oregon’s Marijuana Fund, which consists of tax revenue from the state’s cannabis industry. Future psychedelic laws could copy this arrangement or draw funds from state alcohol or tobacco sales.

Next Steps for Colorado’s Natural Medicine Health Act

On Friday, journalist Chris Walker reported on Colorado’s Natural Medicine Health Act (Proposition 122) for Denver’s 5280 Magazine. In his article, Walker maps out what is known about Proposition 122 and what will be determined during its eighteen-month implementation period.

Proposition 122’s personal use section reduces criminal penalties associated with five psychedelics, including psilocybin, psilocin, mescaline, ibogaine, and dimethyltryptamine (DMT). Coloradans may soon grow, store, consume, and share plants and fungi containing these substances. But there are limitations. For instance, cultivation must occur at home, public ingestion is prohibited, and people cannot receive payment for sharing psychedelics.

What we don’t know is the amount of each substance a person may possess before violating the law. Proposition 122 limits possession to “amounts necessary” for sharing in a variety of contexts such as “counseling, spiritual guidance,” or “beneficial community-based use.” But nobody knows what these terms mean because Proposition 122 does not define them. Consequently, police and courts will determine what the actual limits are and when they apply. Attorneys who drafted the bill don’t seem worried about these ambiguities or the burdens they place on Coloradans. However, some communities may be disproportionately impacted, particularly those in counties that opposed Proposition 122.

It also remains unclear who will make rules for implementing Proposition 122’s regulated access program. The law puts Colorado’s Department of Regulatory Agencies (DORA) in charge of drafting rules. However, though rumors circulate, DORA has not announced who will head its nascent psychedelic program. Moreover, next month, Governor Jared Polis will appoint members to an advisory board that will make recommendations to DORA. Proposition 122 sets out general requirements for the board’s composition, but ordinary Coloradans might be at a disadvantage.

Members of the Natural Medicine Colorado campaign, which promoted passage of Proposition 122, have expressed interest in joining the advisory board. They include life coach and hypnotherapist Veronica Lightening Horse Perez and attorney Sean McAllister. Perez told Walker the campaign is contacting people it feels would be valuable contributors to the board and urging them to apply.

Coloradans should be skeptical of the campaign’s influence over the advisory board. A political organization called New Approach PAC funds the campaign. It also oversaw the drafting of Proposition 122 and spent millions of dollars to pass it. New Approach’s Chief of Staff Taylor West told Walker she has no knowledge of who’s thrown their hat into the ring for board membership. But some Coloradans tell me her campaign has already submitted a roster of preferred candidates to the governor’s office.

In addition to funding the Proposition 122 campaign, New Approach funded the campaign to pass Oregon’s psychedelic law, Measure 109, which voters approved in 2020. For two years, New Approach staff have influenced Measure 109’s implementation through a lobbying firm called the Healing Advocacy Fund, which meets privately with Oregon regulators and advisory board members to shape their psilocybin policies. The Fund’s influence spawned controversy and conflicts of interest that marred Measure 109’s implementation.

This process is now repeating itself in Colorado. West told Walker: “[I]t’s really important to have an outside organization of people [like the Healing Advocacy Fund] who are advocates for the initiative . . . That’s a collaborator that you want to have if you’re a rule maker or regulator or advisory board member.” But Coloradans should ask whether New Approach and the Healing Advocacy Fund’s influence is in their best interest. Colorado is a pioneer of psychedelic law, policy, and practice. It need not rely on out-of-state organizations or political insiders to shape its psychedelic policies.

As Governor Polis considers candidates for Proposition 122’s advisory board, he should appoint members who are unaffiliated with New Approach, the Healing Advocacy Fund, or the Proposition 122 campaign. They’ve had their fair share of influence already, and Polis should give Coloradans who have not been paid by these organizations to have seats at the table. He should also screen candidates for other personal and professional conflicts of interest that might bias their decisions. DORA should prohibit board members from founding companies that will be regulated by the agency’s rules (a widespread problem on Oregon’s advisory board).

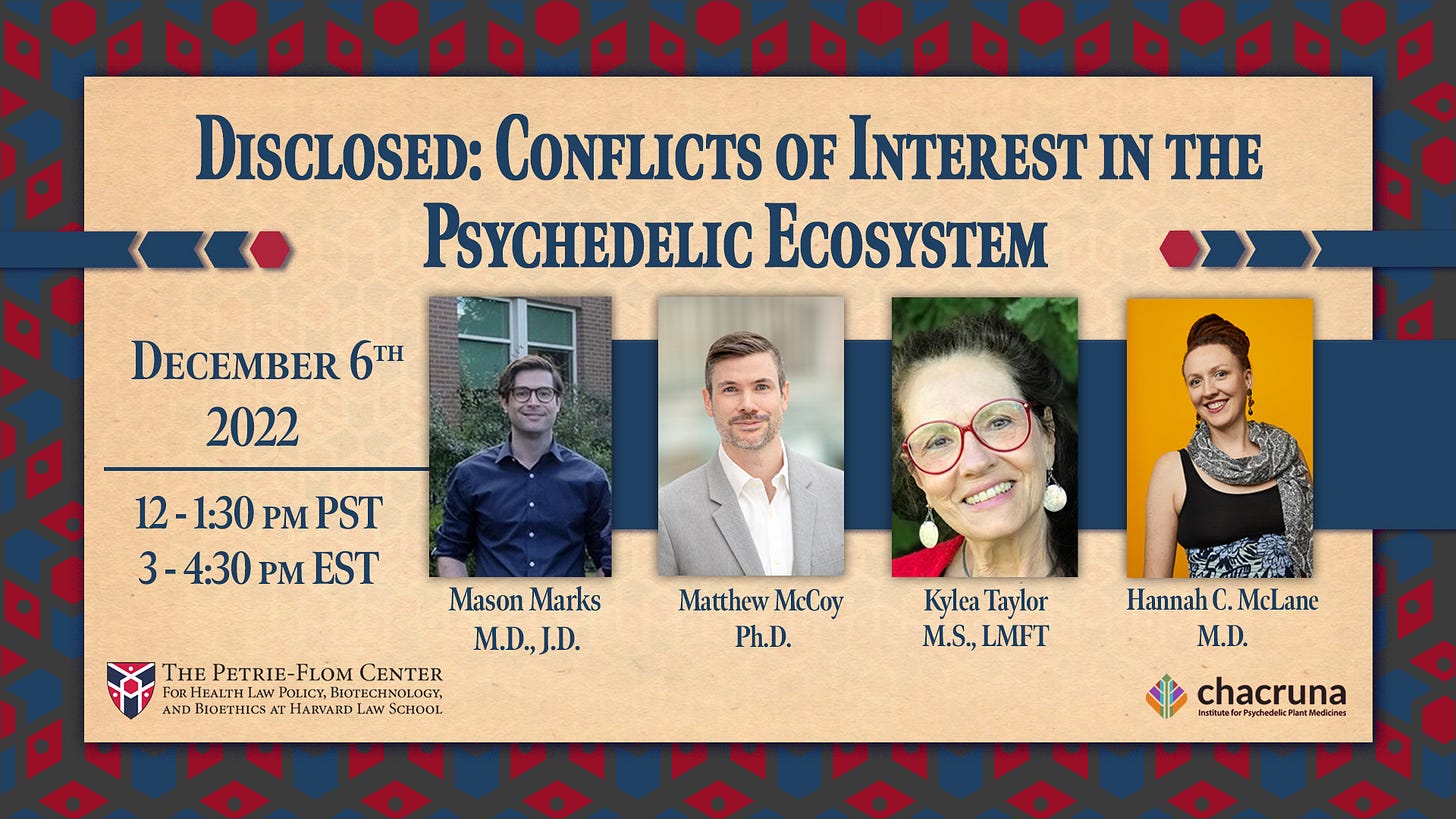

There’s nothing wrong with profiting from one’s expertise, but there will be plenty of time for that after Colorado’s board members make recommendations and complete their terms of service. Further, board members should disclose any relevant conflicts before voting and recuse themselves when appropriate. This policy was supposed to be implemented on Oregon’s advisory board, but it was not followed. For a detailed discussion of conflicts of interest in the psychedelic ecosystem, watch this recent panel co-hosted by the Project on Psychedelics Law and Regulation (POPLAR) at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School.

Colorado’s implementation of Proposition 122 will likely draw more national and global attention than Oregon’s program drew over the past two years. Public interest in psychedelics is growing, and the spotlight will be fixed on DORA and its advisory board. Consequently, Colorado must do better than Oregon and learn from its mistakes. That starts with being transparent, accountable, and proactive as Proposition 122’s rulemaking process begins.

A Fresh Take on the Natural Medicine Health Act

In case you missed it, last week I published my latest thoughts on Colorado’s Natural Medicine Health Act (Proposition 122) with contributions from Oregon attorney Jon Dennis.

I explain how Proposition 122 can accommodate a variety of regulated access models, including the religious use of psilocybin, home delivery and administration, and dispensary sales. I also describe important differences between Oregon’s Measure 109 and Proposition 122. For instance, Measure 109 and the Oregon Health Authority’s draft rules create physical and legal barriers between psilocybin businesses and healthcare services and facilities.

In contrast, Colorado’s Proposition 122 blurs the lines between psilocybin services and medical services and facilities. Blurring these lines jeopardizes Colorado’s program and puts businesses and participants at risk. However, the Natural Medicine Health Act is flexible enough to allow DORA to minimize that risk. I’ll have more to say on that soon.

Portland’s Shroom House Adds to Psilocybin Confusion

Earlier this month, the media became enamored with Shroom House, an illegal storefront on Portland’s busy Burnside Street. Lines wrapped around the block as customers waited hours to purchase dried psilocybin mushrooms. Many attempted to guess when police would shut Shroom House down. Others thought that might never happen.

Ballot Measures 109 and 110 have caused significant confusion in Oregon. Measure 109 creates a regulated program for supervised psilocybin use at licensed service centers, and Measure 110 reduces criminal penalties associated with small amounts of psilocybin and other controlled substances. However, neither measure allows for retail stores like Shroom House.

Evan Segura, former president of the Portland Psychedelic Society, explained why people are confused. “If you ask the average person in Oregon what Measure 109 did, most don’t know,” Segura told Portland’s Willamette Week. “The Oregon Health Authority has really botched the public education opportunity they’ve had the last two years,” he said. “People are so confused about what is going to happen here.”

Because Oregon’s psychedelic laws have become so heavily politicized, it can be difficult to get a read on what they actually achieve. A lack of unbiased educational campaigns and an abundance of superficial media reports have contributed to the confusion. Some believe psilocybin mushrooms have been fully legalized in Oregon. Others think only medical use is permitted. But Oregon’s psilocybin laws are more accurately described as a supervised form of recreational use. Regardless of the truth, Shroom house captured the public’s imagination.

After about a week of nonstop media attention, police finally raided the shop on December 8th. In the early morning hours, they seized $13,000 cash and a large volume of suspected psilocybin products. Two individual were later charged with numerous felony counts.

Illegal mushroom shops have opened throughout North America, including in San Francisco, Vancouver, and Toronto. In Oregon, Shroom House appeared to fill a gap between Measures 109 and 110. Psilocybin service centers licensed under Measure 109 won’t open until mid-to-late 2023, and many worry their services might cost thousands of dollars, beyond the reach of many Oregonians. Meanwhile, Measure 110 reduces criminal penalties for possessing small amounts of psilocybin but offers no means for people to acquire the substance. Shroom House was a stopgap, filling an unmet need reflected in interviews with the shop’s queued customers, some of whom recounted driving hours to reach the store.

While Oregonians wait to see when Measure 109’s psilocybin services open, and how much they will cost, more illegal mushroom vendors may pop up. Demand might even spike if Measure 109’s services are prohibitively expensive.

Recent Event Recordings

WATCH NOW: Disclosed: Conflicts of Interest in the Psychedelic Ecosystem

WATCH NOW: Informed Consent in Psychedelic Therapy and Research: Why Is It So Complicated?

*The views expressed on Psychedelic Week do not represent the views of POPLAR at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School or the Florida State University College of Law. Psychedelic Week is an independent project unaffiliated with these programs and institutions.

Mason Marks, MD, JD is the Florida Bar Health Law Section Professor at the Florida State University College of Law. He is the senior fellow and project lead of the Project on Psychedelics Law and Regulation (POPLAR) at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School and an affiliated fellow at the Information Society Project at Yale Law School. Marks teaches constitutional law, administrative law, drug law, and psychedelic law, . Before moving to Florida, he served on the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board where he chaired its Licensing Subcommittee. Marks has drafted drug policies for state and local lawmakers. His forthcoming book on psychedelic law and politics will be published by Yale University Press. He tweets at @MasonMarksMD and @PsychedelicWeek.