Opposing Oregon's Psychedelic Data Surveillance Bill SB 303

On February 27, the Oregon Senate Committee on Health Care held a hearing on Senate Bill 303. I submitted testimony opposing the bill

On December 27, the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) published final rules for the state’s psilocybin services program. Less than two weeks later, Senator Elizabeth Steiner introduced a bill to override their client confidentiality provisions. Senate Bill 303 (SB 303) would put psilocybin clients and service centers under mandatory government surveillance.

On Monday, February 27, the Oregon Senate Committee on Health Care heard oral testimony on Senate Bill 303. This committee will receive written comments at this link until 1pm PT on March 1.

As of last night, six people had submitted testimony in support of the bill, twenty-four submitted testimony in opposition, and four commentors listed their position as neutral or unknown.

The following is my testimony submitted on March 1 in opposition to SB 303.

Date: March 1, 2023

To: Oregon Senate Committee on Health Care

Re: SB 303 and Amendment

Dear Chair Patterson, Vice-Chair Hayden, and Members of the Committee:

I encourage you to vote against SB 303 in its original and amended forms. I am a medical doctor and a law professor who studies health privacy and the regulation of controlled substances, including psychedelics.

I oppose SB 303 because it is unnecessary—everything it purports to do can already be done voluntarily under rules adopted by the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) in December of 2022. Further, SB 303 adds unnecessary expense to an overbudget government program, it overburdens aspiring psilocybin businesses, and it exposes clients and business owners to unnecessary social and legal risks without improving client safety.

Before I explain further, I must point out inaccuracies in Senator Steiner’s February 27 testimony regarding SB 303. With all due respect to Senator Steiner, based on her testimony, she appears to misunderstand what is allowed under Measure 109 (the Oregon Psilocybin Services Act) and relevant OHA regulations. Senator Steiner testified that voters approved Measure 109 “for therapeutic use only,” and that later this year, Oregon psilocybin services “will be open to clients who want to seek this as an appropriate therapy.” These statements are inaccurate. In fact, the therapeutic use of psilocybin is expressly prohibited by current OHA rules, which reflect limitations imposed by Measure 109. This comes as a surprise to many people because the Healing Advocacy Fund led by Sam Chapman has spent significant time and money framing Oregon’s psilocybin services as a medical program when the OHA’s rules forbid therapeutic use. Unfortunately, many media outlets have perpetuated this misconception.

Per OHA rules, which are codified as O.R.S. Chapter 475A, psilocybin facilitators are prohibited from diagnosing or treating health conditions, and facilitators and service centers are forbidden from making health-related claims. Psilocybin service centers may not be located within healthcare facilities, and if facilitators hold healthcare licenses (e.g., in fields such as nursing or psychology) in addition to their psilocybin facilitator licenses, they are prohibited from exercising the privileges of their healthcare licenses while acting as psilocybin facilitators. In other words, Oregon’s psilocybin services are non-therapeutic by statute and administrative rule. Consequently, Senator Steiner’s claim that SB 303’s data collection mandate will establish the efficacy of psilocybin therapy in Oregon is misguided.

At the February 27 hearing, Chair Patterson asked Senator Steiner and Dr. Bruce Goldberg about the purpose of SB 303’s data collection mandate. “So, this study is to look at the safety and efficacy in specific health conditions? Am I correct?” asked Chair Patterson. “Chair Patterson, that’s correct,” responded Dr. Goldberg.

If the Committee is contemplating Senator Steiner’s proposal, the Committee should ask her and Dr. Goldberg to account for the discrepancies between their testimony and what is allowed under the OHA’s psilocybin regulations. Because psilocybin facilitators cannot diagnose or treat psilocybin clients, nor make medical claims, Senator Steiner’s and Dr. Goldberg’s testimony misrepresents SB 303 and the Oregon psilocybin program while potentially misleading the Committee.

I now return to why SB 303 is unnecessary. Apart from the fact that Measure 109 created a non-therapeutic program, and assessing the clinical efficacy of a non-therapeutic program makes little sense, everything proposed by SB 303 can be achieved under current OHA regulations (O.R.S. Chapter 475A).

The OHA spent two years, and millions in taxpayer dollars, making rules for implementing Measure 109. During the rulemaking process, the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board (the “Advisory Board”) made recommendations to the OHA regarding what data should be collected during client intake and the subsequent provision of psilocybin services.

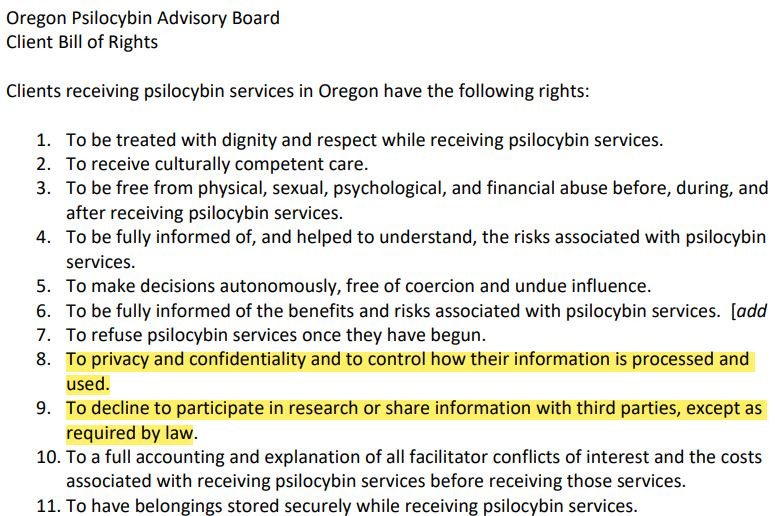

In May 2022, the Advisory Board, which includes physician-researchers from Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU), unanimously recommended that clients have the right to control their data and how it is used, including whether it is shared with third parties outside the service center (see proposed Client Bill of Rights below).

The right proposed by the Advisory Board applied to all client data regardless of whether it was stripped of personal identifiers (“de-identified”). The Advisory Board also recommended a duty of confidentiality for psilocybin facilitators, requiring them to “maintain the confidentiality of client information to the greatest extent possible.”

Under pressure from lobbyist Jack Dempsey and the Healing Advocacy Fund, the OHA initially overruled the Advisory Board’s recommendations on client confidentiality. However, in response to subsequent public input, the agency adopted most of the Advisory Board’s recommendations in its final rules, published in December 2022. Under these regulations, if service centers wish to share clients’ deidentified data with third parties, they must present clients with a disclosure form specifying who will receive their deidentified data and how it will be used. Clients can then choose to opt-out of data sharing and none of their deidentified data will be shared outside a service center. This rule respects the will of Oregon voters who approved Measure 109 with robust client confidentiality protections. Those protections apply not only to data that “may be used to identify a client,” but also to “any communication” made by clients while receiving psilocybin services,” which includes deidentified data.

Under the existing OHA rules, researchers at OHSU or elsewhere can partner with psilocybin service centers to collect all the data points described by Steiner’s SB 303 and the proposed amendment. The only difference is that under current OHA rules, clients must receive the data disclosure form and be given the opportunity to decline to participate.

You have received testimony from Senator Steiner and Sam Chapman stating that without SB 303, “there will be no mechanism” to understand whether Oregon’s psilocybin services are effective. That simply is not true. Voluntary data collection, following adequate client disclosures, is sufficient to learn a great deal about the program and make improvements over time. If statisticians and epidemiologists required data from all members of each population they study to draw meaningful conclusions, they would achieve very little. Instead, they rely on statistical sampling to infer characteristics of entire populations from samples drawn from their members. The psilocybin clients who consent to share their data in Oregon will serve as samples from which meaningful inferences can be drawn.

Current OHA psilocybin regulations balance the value of voluntary data collection with the need to respect client autonomy and confidentiality. These issues were extensively debated during the OHA’s two-year implementation period. Moreover, while acknowledging the risks of extensive data collection, and the fact that Measure 109 created a non-medical program, the Advisory Board and OHA concluded that service centers should collect only the minimum amount of client information necessary to promote safe psilocybin experiences.

SB 303 disregards the countless hours of deliberation over how much data service centers must collect. These discussions included physicians, nurses, therapists, members of BIPOC and LGBTQ+ communities, regulators, and attorneys from within Oregon and around the world. The resulting rules were evaluated by the public, the OHA, and the agency’s Rules Advisory Committees. Enacting SB 303 sends the message that their deliberation at significant public expense did not matter, and it requires taxpayers to sink additional funds into an already overbudget government program.

During the Advisory Board’s final meeting of 2022, OHA officials announced that the agency was running out of funds to administer the psilocybin program. Consequently, the OHA planned to ask the legislature for additional public funds. Specifically, the OHA requested $6.5 million in general funds to operate the psilocybin program for one year starting July 1, 2023. The data collection mandate proposed by SB 303 will cost the OHA additional money, pushing an essentially bankrupt program further into the red.

To make up for this deficit, the OHA will either have to raise annual psilocybin licensing fees, which are already exorbitant at $10,000 for most service centers and $2,000 for most facilitators. Alternatively, Oregon taxpayers must foot the bill. In his testimony dated February 1, the OHA’s Andre Ourso acknowledges that SB 303’s data collection requirements would add significant costs to the psilocybin program’s administration and could interfere with the OHA’s ability to ensure compliance with existing regulations.

According to Ourso, “[t]he client information required by SB 303 is extensive and could be seen as invasive for many clients, especially for clients who belong to communities that have been subject to disproportionate enforcement of criminal laws or unethical research practices. Therefore, the data collection required by SB 303 is likely to discourage members of these communities from seeking psilocybin services.” Even worse, though SB 303 already includes a long list of data points that far exceeds what OHA and its Advisory Board required, the bill would give OHA virtually unlimited power to add whatever data points it likes in the future.

If the goal of SB 303 is to increase access, and its extensive data collection practices discourage members of marginalized communities from participating, then SB 303 frustrates its own purpose and should be rejected. Discouraging people from participating in the regulated psilocybin program incentivizes them to obtain psilocybin from illicit markets, where safety is far less assured.

Ourso adds, “[t]he same [data collection] requirements may also discourage psilocybin facilitators who belong to these communities from participating in the regulated space.” That is problematic because there are already too few license applications to support the psilocybin program, which is required to be self-sustaining, and is already far short of that goal. Because SB 303’s burdensome data collection discourages aspiring service center operators from becoming licensed, the bill will contribute to the psilocybin program’s worsening budget shortfall.

Oregon taxpayers should not be burdened with additional expense when they have already paid millions for the OHA’s two-year rulemaking process that concluded in December. The result of that process was a well-reasoned rule, which honors voters’ will and was the product of extensive public deliberation by the Advisory Board, OHA’s Rule Advisory Committee, and numerous public listening sessions. Now a small number of individuals led by Senator Steiner and lobbyists with the Healing Advocacy Fund wish to overturn the methodical, collaborative work of the OHA, its Advisory Board, and impacted communities.

If researchers at OHSU or elsewhere wish to collect data from psilocybin clients in Oregon, they are free to do so under ORS Chapter 475A unless clients specifically opt out. In other words, without SB 303 and the proposed amendment, OHSU and other organizations can seek grants from federal agencies or private donors and partner with psilocybin service centers to collect data and conduct research. They need not further burden Oregon taxpayers.

It is worth noting that many people who submitted testimony in support of SB 303, including Senator Steiner, Dr. Goldberg, and Dr. Gideons are paid employees of OHSU, which directly benefits from SB 303. Additional supporters of the bill are paid by the Healing Advocacy Fund, which orchestrated SB 303. For instance, you heard from staff of the facilitator training program Inner Trek, which has received thousands of dollars from the Healing Advocacy Fund.

In his written testimony, Sam Chapman says SB 303 was the product of community input. However, the Oregon communities he consulted overwhelmingly oppose SB 303 and are represented in the testimony opposing the bill.

Aspiring psilocybin business owners do not want SB 303 because it burdens them with unnecessary obligations and expenses, making an already precarious business proposition even more uncertain. Psilocybin clients do not support the bill because they don’t want their personal information, and evidence that they violated federal law, collected and stored within a state database. Voters don’t want SB 303 because it overrides the robust confidentiality protections of the ballot initiative they approved, while creating an added expense for taxpayers. You have even heard from healthcare providers who oppose this bill because valuable insights on the psilocybin program can be gleaned from clients and service centers who voluntarily provide data.

The Healing Advocacy Fund has ulterior motives for SB 303’s enactment. Sam Chapman has approached groups outside Oregon to sell them on the value of Oregon psilocybin client data. In a November presentation, Chapman and colleague Graham Boyd, Director of New Approach PAC, enticed Massachusetts researchers with the prospect of expanding their data sets with Oregon psilocybin client information.

SB 303 states that psilocybin client data cannot be sold. However, there are other ways to profit from data, including selling access to it or patenting inventions that result from it. Facebook made billions from user data without ever selling the information. In recent emails to Oregon psilocybin industry participants, Chapman acknowledged that data collected through SB 303 could be made available to groups outside Oregon and OHSU, including commercial stakeholders. During an Advisory Board meeting in 2022, Board member and OHSU researcher Todd Korthuis acknowledged that data collected from psilocybin clients would be of great commercial interest to for-profit companies.

The Senate Committee on Health Care can honor the will of Oregon voters and protect psilocybin clients from attempts to exploit their sensitive information. Please reject SB 303 as introduced and amended.

In addition to the above testimony, I support the arguments raised by the Oregon Psilocybin Services Collaborative Community (OSPCC) in its public comment document.

Sincerely,

Mason Marks, MD, JD

*The views expressed on Psychedelic Week do not represent the views of POPLAR at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School or the Florida State University College of Law. Psychedelic Week is an independent project unaffiliated with these programs and institutions.

Mason Marks, MD, JD is the Florida Bar Health Law Section Professor at the Florida State University College of Law. He is the senior fellow and project lead of the Project on Psychedelics Law and Regulation (POPLAR) at the Petrie-Flom Center at Harvard Law School and an affiliated fellow at the Information Society Project at Yale Law School. Marks teaches drug law, psychedelic law, constitutional law, and administrative law. Before moving to Florida, he served on the Oregon Psilocybin Advisory Board where he chaired its Licensing Subcommittee. Marks has drafted drug policies for state and local lawmakers. His forthcoming book on psychedelic law and politics will be published by Yale University Press. He tweets at @MasonMarksMD and @PsychedelicWeek.